Constitutional Convention

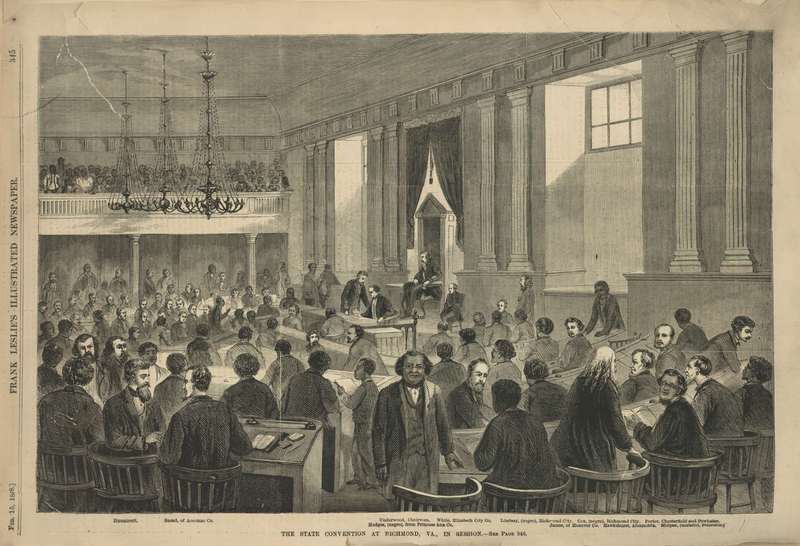

The constitutional convention met in the chamber of the House of Delegates in the Capitol in Richmond from December 3, 1867, through April 17, 1868. Known as the Underwood Convention, after its president, Radical Republican federal judge John C. Underwood, the constitution it produced is also sometimes known as the Underwood Constitution.

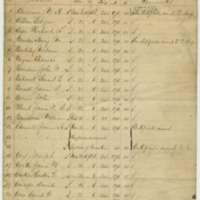

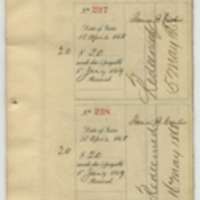

Twenty-four of the delegates were African Americans. They and other supporters of radical Reconstruction held a majority of the seats. This first page of the official convention roster contains the names of some of the African American delegates: William H. Andrews, Thomas Bayne, James W. D. Bland, William Breedlove, John Brown, David Canada, James B. Carter, and Joseph Cox. During the convention, hostile white politicians and editors condemned the convention and its members. The Richmond Daily Enquirer and Examiner of December 13, 1867, referred to the delegates as a "vile rabble." The African Americans were the objects of much abuse. Even though some of them were unable to read and write, others were educated, highly intelligent, and able advocates for the rights of the freedpeople. Thomas Bayne, who had escaped from slavery in Norfolk before the Civil War and become a dentist, was an eloquent advocate for African American suffrage and for public education.

The convention approved the constitution and the president signed it on April 17, 1868, the seventh anniversary of the vote in the Convention of 1861 in favor of secession. The constitution reformed local government on the more democratic model of the New England township; it required the General Assembly to create a statewide system of free public schools for all children; it granted the governor the right to veto bills that the assembly had passed; and it granted the vote to "Every male citizen of the United States, twenty-one years old," except some supporters of the Confederacy. The draft constitution disfranchised men who had held public office before the Civil War—and taken an oath of allegiance to the United States at that time—who later had "engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof." That delayed the ratification referendum until after a committee of white political leaders in Virginia reached an agreement with the president and members of Congress to allow those clauses to be voted on separately. In July 1869, when the voters ratified the constitution by a vote of 210,585 to 9,136, they rejected the clauses disfranchising former Confederates.

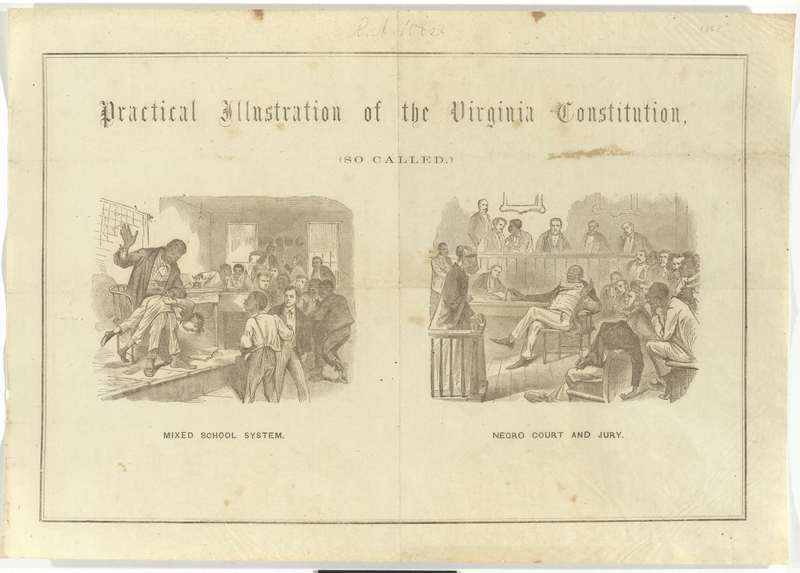

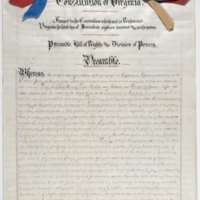

Opponents of the constitution spread misinformation and produced political broadside such as this one to frighten white Virginians into voting against ratification of the constitution by spreading fears that African Americans would be able to beat white children in the new public schools or serve as jurors in trials involving white ladies and gentlemen.

The constitution remained in effect until 1902, when a new state constitution replaced it and authorized the General Assembly to revise voting and registration laws to deprive African Americans of the right to vote and hold public office.